Description

Introduction: The farm production system is defined as the combination of productive activities and the means of production (Mazoyer and Roudart, 2002). It involves resources and farming activities that help achieve the farm's objectives efficiently (Mazoyer, 2002). According to Landais (1992), a livestock production system consists of elements interacting dynamically, organized to enhance resources through domestic animals, aiming to produce milk, meat, hides, and manure, or other objectives. Field investigations helped identify and characterize livestock farming systems in the study region. The analysis focused on the farm's components, including human, animal, and land. Statistical and parametric data analysis methods were applied to describe these systems. To better understand this complex system, Lhoste (1987) proposed an explanatory diagram to offer a global approach, emphasizing the need for a multidisciplinary perspective without overemphasizing zootechnical aspects.

Materials and Methods

Study Area: The study is set in the western high steppe plains of Algeria, specifically in the Ksour mountains, located in the south-west of the wilaya of Nâama (Fig. 01). The commune of Sfissifa, about thirty kilometers from Ain Sefra, is an area with low development potential due to its challenging terrain and its location as a border zone with Morocco. Ain Sefra's larger size also makes it a more attractive center. Sfissifa is experiencing depopulation, as the population recorded in 1987 (8,479 inhabitants) has declined compared to the most recent census (DPSB, 2024).

Methodology: To carry out our study, we adopted a methodological approach starting with bibliographic research, consulting various sources such as books, articles, and reports from institutions like the Directorate of Agricultural Services (DAS), the Sfissifa agricultural subdivision, and the Commission for the Development of Agriculture in Saharan Regions (CDARS) to collect information on breeding systems. This was followed by pre-surveys with resource persons to gather additional data on livestock types and other resources in the Sfissifa region. Next, we designed a questionnaire to explore livestock systems in the region. The questionnaire covered general information about the farmers and their herds (size, structure, breeds, etc.), details on the animals (number, reproduction, etc.), farm building characteristics (type, hygiene, etc.), and feed used (types, storage, grazing periods, water availability). Finally, we conducted surveys with 150 randomly selected farmers across different zones, using individual or group interviews. These were held in fields, stables, and homes to ensure comprehensive data collection.

Results: Lhoste (1984) defines the farming system as a set of relationships between three poles: the farmer, the herd, and the land. Our study methodology, based on surveys from a single visit, allowed us to classify farmers according to the size of their herds, aligning with the findings of Kanoun, Muqalati, and Yakhlef (2008). We classified the farmers into three categories based on herd size:C1 (Smallholders): Farmers with herds of ≥100 head. These subsistence farmers primarily sell a few animals locally.C2 (Medium-sized owners): Farmers with 101–500 head, typically more commercial breeders aiming to increase production and sell locally and regionally.C3 (Large landowners): Farmers with over 500 head, operating as breeder-finishers focused on commercial production and national markets. They invest in modern infrastructure and practices.Additionally, farmers were classified into two groups based on their activities: Agro-pastoralists (combining agriculture and livestock farming) and Livestock breeders (focusing solely on livestock). In C1, 14% were Agro-pastoralists, and there were no Livestock breeders. In C2, 48% were Agro-pastoralists, and 18% were Livestock breeders. In C3, 18% were Agro-pastoralists, and 2% were Livestock breeders.In the commune of Sfissifa, the most common breeding system is the sedentary system, which involves 42% of agro-pastoralists and 14% of livestock breeders. The second most common system is the semi-sedentary system, with 30% of agro-pastoralists and 10% of livestock breeders adopting it. The transhumant system is very rare, present in only 4% of agro-pastoralists and absent among livestock breeders.

Regarding the different classes of operators, Class II is the most represented, with 48% of agro-pastoralists and 18% of livestock breeders. Class III is represented by 18% of agro-pastoralists and only 2% of livestock breeders. Class I includes only 14% of agro-pastoralists.

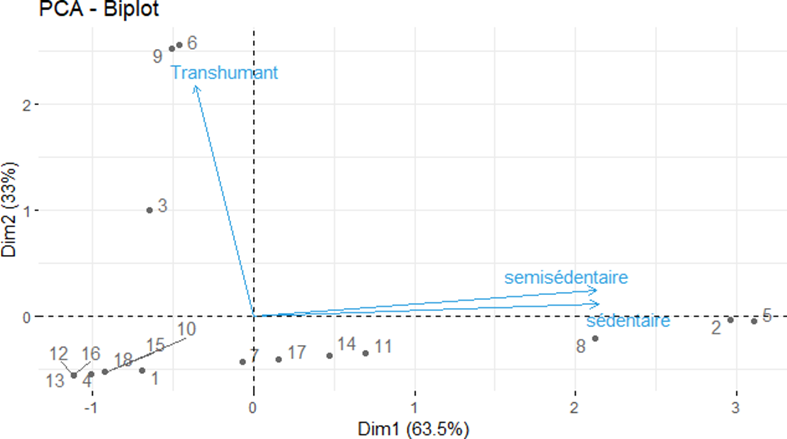

Discussion: After studying the breeding systems in the Sfissifa area through interviews with 150 operators (80% agro-pastoralists and 20% livestock breeders), principal component analysis (PCA) revealed the following:

The first principal component (sedentary breeding system) has a standard deviation of 1.3799 and accounts for 56% of the total variance.

The second principal component (semi-sedentary breeding system) has a standard deviation of 0.9943 and accounts for 40% of the total variance.

The third principal component (transhumant breeding system) has a standard deviation of 0.32768 and accounts for 4% of the total variance.

In cumulative terms, the sedentary system explains 56% of the variance, the combination of sedentary and semi-sedentary systems explains 96%, and the transhumant system accounts for just 4%, bringing the total to 100%. Thus, the sedentary and semi-sedentary systems represent the dominant factors in the variability observed (fig.01).

Conclusion: In the commune of Sfissifa, the sedentary breeding system is the most widely adopted, with 42% of agro-pastoralists and 14% of livestock breeders using it. The semi-sedentary system follows, with 30% of agro-pastoralists and 10% of livestock breeders employing it. The transhumant system is marginal, practiced by only 4% of agro-pastoralists. Class II farmers are the most prevalent, making up 48% of agro-pastoralists and 18% of livestock breeders.

To improve livestock production sustainability and efficiency, it is recommended to provide technical and financial support to farmers using the sedentary system due to its widespread adoption. Incentive strategies could also encourage more farmers to adopt the semi-sedentary system, which appears well-suited to local conditions. Additionally, investigating the obstacles limiting the adoption of the transhumant system could offer insights into farmer reluctance and help identify solutions. Special attention should be given to farmers in classes III and I to boost their productivity and ensure greater economic stability.

FARADJI Khalil, SLIMANI Noureddine, SENOUSSI Abdelhakim

Department of Agricultural Sciences, Faculty of Natural and Life Sciences, Environmental and Health Biology Laboratory, university of El Oued 39000-Algeria

Department of Agricultural Sciences, Faculty of Natural and Life Sciences, Environmental and Health Biology Laboratory, university of El Oued 39000-Algeria

Department of Agricultural Sciences, Faculty of Natural and Life Sciences, Saharan,Bioresources Laboratory: Preservation and Valorisation, university of Ouergla 30000-Algeria.

References:

Bourbouze A.(2000). Pastoralism in the Maghreb: the silent revolution. CIHEAM / IAM (Montpellier). 2000. 19 p. http://www.afpf-asso.org/index/action/page/id/33/title/Les- articles/article/1477.

Bourbouze A.(2006). Livestock systems and animal production in the steppes of North Africa: a reading of the pastoral society of the Maghreb. Science and planetary changes / Drought 17(1): 31-39.

DPSB.(2024). Monograph of the wilaya of Naâma year 2022. Directorate of programming and budgetary monitoring of the wilaya Naâma.

Elloumi M.,Selmi S and Zaibet L.(2011). Economic importance and mutation of sheep production systems in Tunisia. Mediterranean Options: Series A. Mediterranean Seminars; n. 97, 11-21p.

Kanoun-Meguellati A.,et Yakhlef H.(2008). Constraints and adaptation strategies of sheep farmers in a pastoral environment: Case of Djelfa, Algeria. in International conference "Sustainable development of animal production: issues, evaluation and perspectives", Algiers, April 20-21. http://www.ensa.dz/IMG/pdf/actes_du_colloque_3-SE7.pdf.

Kayouli C.(2000). Effects of underfeeding and refeeding on offal weight in Barbary ewes. Small Ruminant Research, Volume 38, Number 1, September 1, 2000, pages 37-43.

Landais E.(1992). The three poles of livestock systems. Research and development notebooks, 32 (2): 3-5. http://cahiers-recherche-developpement.cirad.fr/cd/CRD_32_3-5.pdf.

Lhoste P.(1984). The diagnosis of the livestock system. Research and development notebooks, 3-4: 84-88. http://cahiers-recherche-developpement.cirad.fr/cd/CRD_3-4_84-88.pdf.

Lhoste P.(1987). The agriculture-livestock association: Evolution of the agropastoral system in Sine-Saloum (Senegal). Studies and syntheses of the IEMVT- Maisons-Alfort, 314 p.Livestock Research for Rural Development, Volume 27, Article #132 http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd27/7/mouh27132.html.

Mazoyer M.(2002). Activity and management of agricultural exploitation, in Larousse agricole, 684.

Materials and Methods

Study Area: The study is set in the western high steppe plains of Algeria, specifically in the Ksour mountains, located in the south-west of the wilaya of Nâama (Fig. 01). The commune of Sfissifa, about thirty kilometers from Ain Sefra, is an area with low development potential due to its challenging terrain and its location as a border zone with Morocco. Ain Sefra's larger size also makes it a more attractive center. Sfissifa is experiencing depopulation, as the population recorded in 1987 (8,479 inhabitants) has declined compared to the most recent census (DPSB, 2024).

Methodology: To carry out our study, we adopted a methodological approach starting with bibliographic research, consulting various sources such as books, articles, and reports from institutions like the Directorate of Agricultural Services (DAS), the Sfissifa agricultural subdivision, and the Commission for the Development of Agriculture in Saharan Regions (CDARS) to collect information on breeding systems. This was followed by pre-surveys with resource persons to gather additional data on livestock types and other resources in the Sfissifa region. Next, we designed a questionnaire to explore livestock systems in the region. The questionnaire covered general information about the farmers and their herds (size, structure, breeds, etc.), details on the animals (number, reproduction, etc.), farm building characteristics (type, hygiene, etc.), and feed used (types, storage, grazing periods, water availability). Finally, we conducted surveys with 150 randomly selected farmers across different zones, using individual or group interviews. These were held in fields, stables, and homes to ensure comprehensive data collection.

Results: Lhoste (1984) defines the farming system as a set of relationships between three poles: the farmer, the herd, and the land. Our study methodology, based on surveys from a single visit, allowed us to classify farmers according to the size of their herds, aligning with the findings of Kanoun, Muqalati, and Yakhlef (2008). We classified the farmers into three categories based on herd size:C1 (Smallholders): Farmers with herds of ≥100 head. These subsistence farmers primarily sell a few animals locally.C2 (Medium-sized owners): Farmers with 101–500 head, typically more commercial breeders aiming to increase production and sell locally and regionally.C3 (Large landowners): Farmers with over 500 head, operating as breeder-finishers focused on commercial production and national markets. They invest in modern infrastructure and practices.Additionally, farmers were classified into two groups based on their activities: Agro-pastoralists (combining agriculture and livestock farming) and Livestock breeders (focusing solely on livestock). In C1, 14% were Agro-pastoralists, and there were no Livestock breeders. In C2, 48% were Agro-pastoralists, and 18% were Livestock breeders. In C3, 18% were Agro-pastoralists, and 2% were Livestock breeders.In the commune of Sfissifa, the most common breeding system is the sedentary system, which involves 42% of agro-pastoralists and 14% of livestock breeders. The second most common system is the semi-sedentary system, with 30% of agro-pastoralists and 10% of livestock breeders adopting it. The transhumant system is very rare, present in only 4% of agro-pastoralists and absent among livestock breeders.

Regarding the different classes of operators, Class II is the most represented, with 48% of agro-pastoralists and 18% of livestock breeders. Class III is represented by 18% of agro-pastoralists and only 2% of livestock breeders. Class I includes only 14% of agro-pastoralists.

Discussion: After studying the breeding systems in the Sfissifa area through interviews with 150 operators (80% agro-pastoralists and 20% livestock breeders), principal component analysis (PCA) revealed the following:

The first principal component (sedentary breeding system) has a standard deviation of 1.3799 and accounts for 56% of the total variance.

The second principal component (semi-sedentary breeding system) has a standard deviation of 0.9943 and accounts for 40% of the total variance.

The third principal component (transhumant breeding system) has a standard deviation of 0.32768 and accounts for 4% of the total variance.

In cumulative terms, the sedentary system explains 56% of the variance, the combination of sedentary and semi-sedentary systems explains 96%, and the transhumant system accounts for just 4%, bringing the total to 100%. Thus, the sedentary and semi-sedentary systems represent the dominant factors in the variability observed (fig.01).

Conclusion: In the commune of Sfissifa, the sedentary breeding system is the most widely adopted, with 42% of agro-pastoralists and 14% of livestock breeders using it. The semi-sedentary system follows, with 30% of agro-pastoralists and 10% of livestock breeders employing it. The transhumant system is marginal, practiced by only 4% of agro-pastoralists. Class II farmers are the most prevalent, making up 48% of agro-pastoralists and 18% of livestock breeders.

To improve livestock production sustainability and efficiency, it is recommended to provide technical and financial support to farmers using the sedentary system due to its widespread adoption. Incentive strategies could also encourage more farmers to adopt the semi-sedentary system, which appears well-suited to local conditions. Additionally, investigating the obstacles limiting the adoption of the transhumant system could offer insights into farmer reluctance and help identify solutions. Special attention should be given to farmers in classes III and I to boost their productivity and ensure greater economic stability.

FARADJI Khalil, SLIMANI Noureddine, SENOUSSI Abdelhakim

Department of Agricultural Sciences, Faculty of Natural and Life Sciences, Environmental and Health Biology Laboratory, university of El Oued 39000-Algeria

Department of Agricultural Sciences, Faculty of Natural and Life Sciences, Environmental and Health Biology Laboratory, university of El Oued 39000-Algeria

Department of Agricultural Sciences, Faculty of Natural and Life Sciences, Saharan,Bioresources Laboratory: Preservation and Valorisation, university of Ouergla 30000-Algeria.

References:

Bourbouze A.(2000). Pastoralism in the Maghreb: the silent revolution. CIHEAM / IAM (Montpellier). 2000. 19 p. http://www.afpf-asso.org/index/action/page/id/33/title/Les- articles/article/1477.

Bourbouze A.(2006). Livestock systems and animal production in the steppes of North Africa: a reading of the pastoral society of the Maghreb. Science and planetary changes / Drought 17(1): 31-39.

DPSB.(2024). Monograph of the wilaya of Naâma year 2022. Directorate of programming and budgetary monitoring of the wilaya Naâma.

Elloumi M.,Selmi S and Zaibet L.(2011). Economic importance and mutation of sheep production systems in Tunisia. Mediterranean Options: Series A. Mediterranean Seminars; n. 97, 11-21p.

Kanoun-Meguellati A.,et Yakhlef H.(2008). Constraints and adaptation strategies of sheep farmers in a pastoral environment: Case of Djelfa, Algeria. in International conference "Sustainable development of animal production: issues, evaluation and perspectives", Algiers, April 20-21. http://www.ensa.dz/IMG/pdf/actes_du_colloque_3-SE7.pdf.

Kayouli C.(2000). Effects of underfeeding and refeeding on offal weight in Barbary ewes. Small Ruminant Research, Volume 38, Number 1, September 1, 2000, pages 37-43.

Landais E.(1992). The three poles of livestock systems. Research and development notebooks, 32 (2): 3-5. http://cahiers-recherche-developpement.cirad.fr/cd/CRD_32_3-5.pdf.

Lhoste P.(1984). The diagnosis of the livestock system. Research and development notebooks, 3-4: 84-88. http://cahiers-recherche-developpement.cirad.fr/cd/CRD_3-4_84-88.pdf.

Lhoste P.(1987). The agriculture-livestock association: Evolution of the agropastoral system in Sine-Saloum (Senegal). Studies and syntheses of the IEMVT- Maisons-Alfort, 314 p.Livestock Research for Rural Development, Volume 27, Article #132 http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd27/7/mouh27132.html.

Mazoyer M.(2002). Activity and management of agricultural exploitation, in Larousse agricole, 684.

Open Access

Filling the gap between research and communication ARCC provide Open Access of all journals which empower research community in all the ways which is accessible to all.

Products and Services

We provide prime quality of services to assist you select right product of your requirement.

Support and Policies

Finest policies are designed to ensure world class support to our authors, members and readers. Our efficient team provides best possible support for you.

Follow us